Download Microsoft Visual Studio 2010 Torrent Pirate

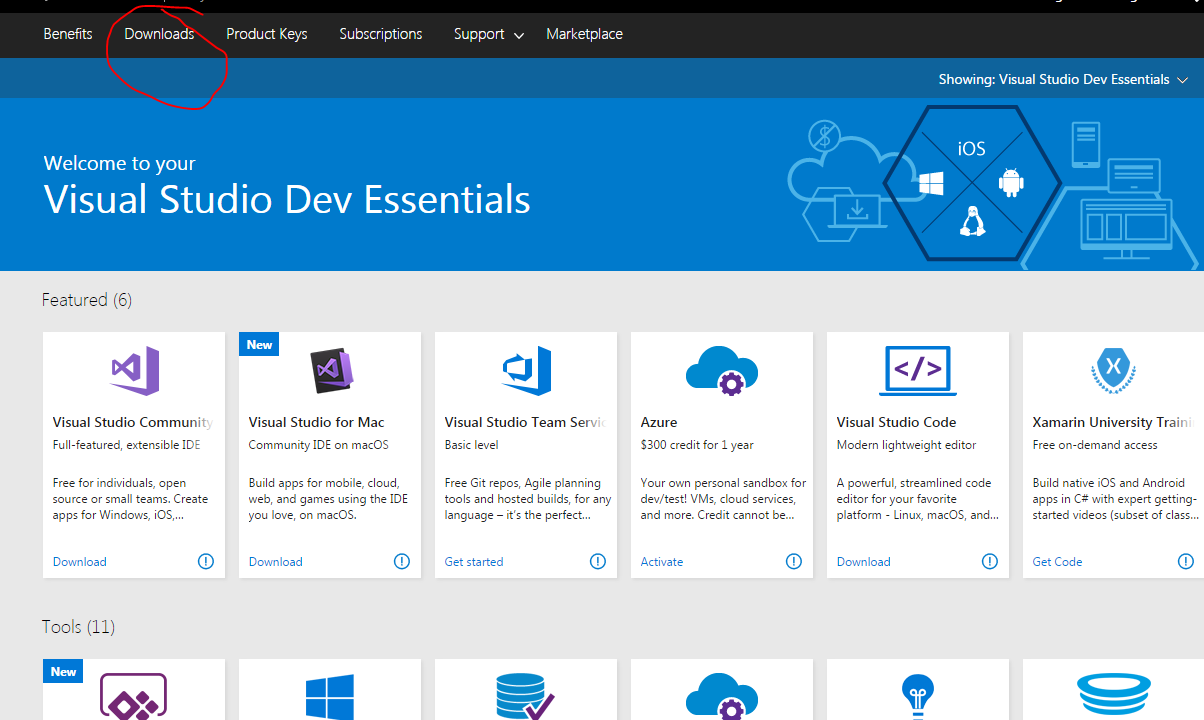

- Microsoft Visual Studio 2010 Ultimate Torrent Download. Microsoft Visual Studio 2010 Ultimate free version. Descargar Visual basic 2010. Microsoft's Visual Studio 2010 Professional is. The Best Video Software for Windows The 3 Free Microsoft Office Photo Editor. Visual Basic 6.0.

- Stay Private and Protected with the Best Firefox Security Extensions The Best Video Software for Windows The 3 Free. Visual Studio 2010. Visual Basic 2010. Download Microsoft Visual Studio 2010 Professional cracked. Use it free of risk. Press the link 'Continue Reading' below the description to get access to Mic.

| Part of a series on |

| File sharing |

|---|

| Technologies |

| Video sharing sites |

| BitTorrent sites |

| Academic/scholarly |

| File sharing networks |

| P2P clients |

| Streaming programs |

| Anonymous file sharing |

| Development and societal aspects |

| By country or region |

| Comparisons |

Visual Studio 2015 Ultimate offline installer ISO. For mysql crack csa w59 pdf free 52 Mark Manson - Models.pdf free download. Visual Studio 2012 Keygen. Visual Studio 2012 Torrent With Crack. Microsoft Visual Studio 2010 Ultimate V10.0.30319.1 RTM - KL Microsoft. Microsoft Visual Studio 2010 Professional Download Full Version, Oem Capture One Pro 8, Textmate 2 Price, Boris Continuum Complete 10 For Adobe AE & PrPro Keygen.

Visual Studio Setup and Installation Question 10 5/21. Visual Studio 2010 Ultimate (final RTM build) Microsoft Visual Studio 2010 Ultimate is the comprehensive suite of application lifecycle management tools for teams to ensure quality results, from design to deployment. Microsoft's Visual Studio 2010 Professional is an integrated solution for developing, debugging, and deploying all kinds of applications. It takes up several.

File sharing is the practice of distributing or providing access to digital media, such as computer programs, multimedia (audio, images and video), documents or electronic books. It involves various legal aspects as it is often used to exchange intellectual property that is subject to copyright law or licensing.

- 2Jurisdictions

- 2.5Germany

- 2.16United States

File hosting and sharing[edit]

File hosting services may be used as a means to distribute or share files without consent of the copyright owner. In such cases one individual uploads a file to a file hosting service, which others may download. Legal history is documented in case law.

For example in the case of Swiss-German file hosting service RapidShare, in 2010 the US government's congressional international anti-piracycaucus declared the site a 'notorious illegal site', claiming that the site was 'overwhelmingly used for the global exchange of illegal movies, music and other copyrighted works'.[1] But in the legal case Atari Europe S.A.S.U. v. Rapidshare AG in Germany (Legal case: OLG Düsseldorf, Judgement of 22 March 2010, Az I-20 U 166/09 dated 22 March 2010) the Düsseldorf higher regional court examined claims related to alleged infringing activity and reached the conclusion on appeal that 'most people utilize RapidShare for legal use cases'[2] and that to assume otherwise was equivalent to inviting 'a general suspicion against shared hosting services and their users which is not justified'.[3] The court also observed that the site removes copyrighted material when asked, does not provide search facilities for illegal material, noted previous cases siding with RapidShare, and after analysis the court concluded that the plaintiff's proposals for more strictly preventing sharing of copyrighted material – submitted as examples of anti-file sharing measures RapidShare might have adopted – were found to be 'unreasonable or pointless'.[4]

In January 2012 the United States Department of Justice seized and shut down the file hosting site Megaupload.com and commenced criminal cases against its owners and others. Their indictment concluded that Megaupload differed from other online file storage businesses, suggesting a number of design features of its operating model as being evidence showing a criminal intent and venture.[5]

Jurisdictions[edit]

Australia[edit]

A secondary liability case in Australia, under Australian law, was Universal Music Australia Pty Ltd v Sharman License Holdings Ltd [2005] FCA 1242 (5 September 2005). In that case, the Court determined that the Kazaa file sharing system had 'authorized' copyright infringement. The claim for damages was subsequently settled out of court.

In the case of AFACT v iiNet which was fought out in the Federal Court, an internet service provider was found not to be liable for the copyright infringement of its users. The case did not, however, create a clear precedent that Australian ISPs could never be held liable for the copyright infringement of their users by virtue of providing an internet connection. AFACT and other major Australian copyright holders have stated their intention to appeal the case, or pursue the matter by lobbying the government to change the Australian law.

Canada[edit]

The Copyright Modernization Act was passed in 2012, and came into effect on 2 January 2015. It provides for statutory damages for cases of non-commercial infringement between $100 and $5 000 and damages for commercial infringement from $500 to $20 000.

China[edit]

The People's Republic of China is known for having one of the most comprehensive and extensive approaches to observing web activity and censoring information in the world.[citation needed] Popular social networking sites such as Twitter and Facebook cannot be accessed via direct connection by its citizens. Mainland China requires sites that share video files to have permits and be controlled by the state or owned by state. These permits last for three years and will need renewal after that time period. Web sites that violate any rules will be subject to a 5-year ban from providing videos online.[6] One of the country's most used file sharing programs, BTChina got shut down in December 2009. It was shut down by the State Administration of Radio Film and Television for not obtaining a license to legally distribute media such as audio and video files.[7] Alexa, a company that monitors web traffic, claims that BTChina had 80,000 daily users. Being one of the primary file sharing websites for Chinese citizens, this shutdown affected the lives of many internet users in China. China has an online population of 222.4 million people and 65.8% are said to participate in some form of file-sharing on websites.[8]

European Union[edit]

On 5 June 2014, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) ruled that making temporary copies on the user's screen or in the user's cache is not, in itself, illegal.[9][10] The ruling relates to the British Meltwater case settled on that day.[11]

The judgement of the court states: 'Article 5 of Directive 2001/29/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 May 2001 on the harmonisation of certain aspects of copyright and related rights in the information society must be interpreted as meaning that the copies on the user’s computer screen and the copies in the internet ‘cache’ of that computer’s hard disk, made by an end-user in the course of viewing a website, satisfy the conditions that those copies must be temporary, that they must be transient or incidental in nature and that they must constitute an integral and essential part of a technological process, as well as the conditions laid down in Article 5(5) of that directive, and that they may therefore be made without the authorisation of the copyright holders.'[12]

The Boy Genius Reportweblog noted that 'As long as an Internet user is streaming copyrighted content online ... it’s legal for the user, who isn’t willfully [sic] making a copy of said content. If the user only views it directly through a web browser, streaming it from a website that hosts it, he or she is apparently doing nothing wrong.'[13]

In November 2009, the European Parliament voted on changes to the Telecoms Package. With regard to file-sharing, MEPs agreed to compromise between protecting copyright and protecting user's rights. A European Parliament statement reads 'A user's internet access may be restricted, if necessary and proportionate, only after a fair and impartial procedure including the user's right to be heard.' EU members were given until May 2011 to implement these changes into their own laws.[14]

Germany[edit]

In Germany, file sharing is illegal and even one copyrighted file downloaded through BitTorrent can trigger €1000 fines or more. The GEMA also used to block many YouTube videos.

Graduated response[edit]

In response to copyright violations using peer to peerfile sharing or BitTorrent the content industry has developed what is known as a graduated response, or three strikes system. Consumers who do not adhere to repeated complaints on copyright infringement, risk losing access to the internet. The content industry has thought to gain the co-operation of internet service providers (ISPs), asking them to provide subscriber information for IP addresses identified by the content industry as engaged in copyright violations. Consumer rights groups have argued that this approach denies consumers the right to due process and the right to privacy. The European Parliament passed a non-binding resolution in April 2008 admonishing laws that would require ISPs to disconnect their users and would prevent individuals from acquiring access to broadband.[15][16]

In a number of European countries attempts to implement a graduated response have led to court cases to establish under which circumstances an ISP may provide subscriber data to the content industry. In order to pursue those that download copyrighted material the individual committing the infringing must be identified. Internet users are often only identifiable by their Internet Protocol address (IP address), which distinguishes the virtual location of a particular computer. Most ISPs allocate a pool of IP addresses as needed, rather than assigning each computer a never-changing static IP address. Using ISP subscriber information the content industry has thought to remedy copyright infringement, assuming that the ISPs are legally responsible for the end user activity, and that the end user is responsible for all activity connected to his or hers IP address.[16][17]

In 2005 a Dutch court ordered ISPs in the Netherlands not to divulge subscriber information because of the way the Dutch content industry group had collected the IP addresses (Foundation v. UPC Nederland). According to Dutch law ISPs can only be ordered to provide personal subscriber data if it is plausible that an unlawful act occurred, and if it is shown beyond a reasonable doubt that the subscriber information will identify the person who committed the infringing act. In Germany court specifically considered the right to privacy and in March 2008 the German Federal Constitutional Court ruled that ISPs could only give out IP address subscription information in case of a 'serious criminal investigation'. The court furthermore ruled that copyright infringement did not qualify as a serious enough offense. Subsequently, in April 2008, the Bundestag (German parliament) approved a new law requiring ISPs to divulge the identity of suspected infringers who infringe on a commercial scale. Similarly, in Sweden, a controversial file sharing bill is awaiting the Riksdag’s approval. The law, which would enter into effect on 1 April 2009, would allow copyright holders to request the IP addresses and names of copyright infringement suspects in order to take legal action against them. The copyright holders, though, should present sufficient evidence of harm to justify the release of information regarding the Internet subscribers.[18] In Italy, the courts established that criminal liability does not extend to file sharing copyrighted material, as long as it is not done for commercial gain. Ruling on a case involving a copyright holder who employed a third party to collect IP addresses of suspected copyright infringers, the Italian Data Protection Authority ruled in February 2008 that the systematic monitoring peer-to-peer activities for the purpose of detecting copyright infringers and suing them is prohibited.[16]

France[edit]

In October 2009, France's highest constitutional court approved the HADOPI law, a 'three-strikes law';[19] however, the law was revoked on 10 July 2013 by the French Government because the punitive penalties imposed on copyright infringers was considered to be disproportionate.[20]

Ireland[edit]

In May 2010, Irish internet provider Eircom have announced they will cut off the broadband connection of subscribers suspected of copyright infringement on peer-to-peer file sharing networks. Initially, customers will be telephoned by Eircom to see if they are aware of the unauthorized downloads. When customers are identified for a third time they will lose their internet connection for 7 days, if caught for a fourth time they will lose their internet connection for a year.[21]

Japan[edit]

File sharing in Japan is notable for both its size and sophistication.[22] The Recording Industry Association of Japan claims illegal downloads outnumber legal ones 10:1.[23]

The sophistication of Japan's filesharing is due to the sophistication of Japanese anti-filesharing. Unlike most other countries, filesharing copyrighted content is not just a civil offense, but a criminal one, with penalties of up to ten years for uploading and penalties of up to two years for downloading.[23] There is also a high level of Internet service provider cooperation.[24] This makes for a situation where file sharing as practiced in many other countries is quite dangerous.

Download Microsoft Visual 2010 Free

To counter, Japanese file sharers employ anonymization networks with clients such as Perfect Dark (パーフェクトダーク) and Winny.

Malaysia[edit]

In June 2011, the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission has ordered the blocking of several websites including The Pirate Bay and several file-hosting websites via a letter dated 30 May to all Malaysian ISPs for violating Section 41 of the Copyright Act 1987, which deals with pirated content.[25]

Mexico[edit]

Mexican law does not currently address non-commercial file sharing, although Mexican legislators have considered increasing penalties for unauthorized file sharing. Broadband usage is increasing in Mexico, and Internet cafes are common,[26]. Due to the relative lack of authorized music distribution services in Mexico, filesharing continues to dominate music access. According to the recording industry in 2010, Internet sharing of music dominated approximately 90% of the total music market in Mexico with peer to peer networks the most dominant form of music copyright infringement.[27]

Netherlands[edit]

According to Dutch law reproduction of a literary, science, or art work is not considered a violation on the right of the creator or performing artist when all of the following conditions have been met:

- The copy has not been made with an (in)direct commercial motive

- The copy's purpose is exclusively for own practice, study or use

- The number of copies is limited

Such a copy is called a 'thuiskopie' or home copy.

Since 2018, following a decision by the Ministry of Justice, there is an organization which guarantees that artists and rights holders get a compensation for copies of their works made for private use.[28] This compensation is levied indirectly through a surcharge on information carriers such as blank CD's, blank DVD's, MP3 Players, and, since 2013, hard drives and tablets.

North Korea[edit]

File sharing in North Korea is done by hand with physical transport devices such as computer disk drives, due to lack of access to the Internet. It is illegal, due to regime attempts to control culture.[29] Despite government repression, file sharing is common, as it is in most other countries.[30]

Download Microsoft Visual Studio 2010 Torrent Pirates

Because official channels are heavily dominated by government propaganda and outside media is banned, illegally traded files are a unique view into the outside world for North Koreans.[30] The most shared media is from South Korea; k-pop and soap operas.[29]

South Korea[edit]

In March 2009, South Korea passed legislation that gave internet users a form of three strikes for unlawful file sharing with the intention of curbing online theft.[31]This is also known as graduated response.As the number of cases of unauthorized sharing increases, the proportion of youth involved has increased. As file shares are monitored, they are sent messages instructing them to stop. If their file sharing continues, their internet connection may be disconnected for up to six months.[32]The force behind this movement is the Korean National Assembly’s Committeeon Culture, Sports, Tourism, Broadcasting & Communications (CCSTB&C). With help from local internet service providers, the CCSTB&C have gainedaccess and formed communication channels to specific file sharing users.[33]

Spain[edit]

In a series of cases, Spanish courts have ruled that file sharing for private use is legal.In 2006, the record industry's attempts to criminalize file sharing were thwarted when Judge Paz Aldecoa declared it legal to download indiscriminately in Spain, if done for private use and without any intent to profit,[34][35] and the head of the police's technology squad has publicly said 'No pasa nada. Podéis bajar lo que queráis del eMule. Pero no lo vendáis.' ('It's ok. You can download whatever you want with eMule. But don't sell it.').[36] There have been demonstrations where the authorities have been informed that copyrighted material would be downloaded in a public place, the last of which took place on 20 December 2008.[37] No legal action was taken against the protestors.[38][39][40][41][42] In another decision from May 2009,[43] a judge ruled in favor of a person engaged in the private, non-commercial file-sharing of thousands of movies, even though the copying was done without the consent of the copyright owners.

The Spanish Supreme Court has ruled that personal data associated with an IP address may only be disclosed in the course of a criminal investigation or for public safety reasons. (Productores de Música de España v. Telefónica de España SAU).[16]

It has been reported that Spain has one of the highest rates of file-sharing in Europe.[44] Over a twelve-month period there were 2.4 billion reported downloads of copyrighted works including music, video games, software and films in Spain. Statistics for 2010 indicate that 30% of the Spanish population uses file-sharing websites, double the European average of 15%.[44]

Record labels would have it that this has had a negative impact on the industry, with investment drying up, according to IFPI head John Kennedy. In 2003, for instance, 10 new Spanish artists appeared in the top 50 album chart, but in 2009 not a single new Spanish artist featured in the same chart. Album sales dropped by two-thirds over a period of five years leading up to 2010. 'Spain runs the risk of turning into a cultural desert ... I think it's a real shame that people in authority don't see the damage being done.'[45]

However, the Spanish Association of Music Promoters (APM) states that 'Music is alive,' as despite the decrease in record sales the revenues from concert ticket sales has increased 117% over the last decade, from €69.9 million to €151.1 million in 2008. The number of concerts doubled from 71,045 in 2000 to 144,859 in 2008, and the number of people attending concerts increased from 21.8 million in 2000 to over 33 million in 2008.[46]

Despite the troubles weathered by the entertainment industry, file sharing and torrent websites were ruled legal in Spain in March 2010. The judge responsible for the court ruling stated that 'P2P networks are mere conduits for the transmission of data between Internet users, and on this basis they do not infringe rights protected by Intellectual Property laws'.[47]

On 20 September 2013, the Spanish government approved new laws that will take effect at the beginning of 2014. The approved legislation will mean that website owners who are earning 'direct or indirect profit,' such as via advertising links, from pirated content can be imprisoned for up to six years. Peer-to-peer file-sharing platforms and search engines are exempt from the laws.[48]

Since January 2015, Vodafone Spain blocks thepiratebay.org as requested by the Ministry of Interior. And since 29 March 2015 thepiratebay is blocked on multiple URLs from all ISPs[111]

United Kingdom[edit]

Around 2010, the UK government's position was that action would help drive the UK’s vital creative and digital sectors to bolster future growth and jobs.[49] According to a 2009 report carried out by the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry95 per cent of music downloads are unauthorised, with no payment to artists and producers.[50] Market research firm Harris Interactive believed there to be 8.3 million file sharers in the UK. Moreover the BPI claimed that in 1999 UK music purchases totaled £1,113 million but had fallen to £893.8 million in 2008.[51] The Digital Economy Act 2010 received Royal Assent on 9 April 2010.[52] But subsequently its main provisions were never legislatively passed.

- Historical situation prior to 2010

Previous cases in the UK have seen internet users receive bills of £2500 for sharing music on the internet.[53]

- Digital Economy Act 2010

The Digital Economy Bill proposed that internet service providers (ISPs) issue warnings by sending letters to those downloading copyrighted files without authorization. Following this, the bill proposed that ISPs slow down or even suspend internet access for repeat offenders of unauthorized file sharing. The bill aimed to force internet service providers to disclose the identities of those offenders as well as making conditions for the regulation of copyright licensing. The Digital Economy Bill incorporated a graduated response policy despite the alleged file sharer not necessarily having to be convicted of copyright offences.[54] The bill also introduced fines of up to £50,000 for criminal offences relating to copyright infringement – for example if music is downloaded with intent to sell. The high penalty is considered to be proportionate to the harm caused to UK industries.[55] An appeals process exists whereby the accused can contest the case however, the concern has been expressed that this process will be costly and that, in requiring the individual to prove their innocence, the bill reverses the core principles of natural justice.[56] Similarly, a website may be blocked if it is considered that it has been, is being, or is likely to be used in connection with copyright infringement[57] meaning that a site does not actually have to be involved in copyright infringement – rather intent must be proved.

The Act was seen as controversial, and potentially creating serious repercussions for both file sharers and internet service providers.[58] The bill was met with a mixed response. Geoff Taylor of the BPI claims the bill is vital for the future of creative works in the UK.[56] The Conservative party spokesman for Culture and Media stated that those downloading should be given a criminal record. Conversely, the Liberal Democrat party spokesman for Culture and Media claimed the bill was reckless and dangerous stating that children could unwittingly be file sharing causing an entire family to lose their internet connection. In addition to this, there was concern that hackers may access internet connections to download files and leave the bill payer responsible. Specific concerns raised included:

- Providers of public Wi-Fi access is uncertain. Responsibility for breaches could be passed on to the provider due to the difficulty in identifying individual users. The internet provider therefore may risk losing internet access or facing a hefty fine if an infringement of copyright takes place. Many libraries and small cafés for example may find this impossible to adhere to as it would require detailed logging of all those requiring internet access. In libraries in particular this may provide challenges to the profession’s importance of user privacy and could force changes in future policies such as Acceptable Use Policies (AUP). Public libraries utilise AUPs in order to protect creative works from copyright infringement and themselves from possible legal liability. However, unless the AUP is accompanied by the provision of knowledge on how to obey laws it could be seen as unethical, as blame for any breaches is passed to the user.[59]

- Hospitality sector - may also be affected by the Digital Economy Act. The British Hospitality Association has stated that hotels would have particular problems in providing details of guest’s internet access to Internet Service Providers and entire hotels may face disconnection. They have also expressed their concern that an individual's actions may lead to such a drastic outcome.[60]

- Internet service providers were also hostile towards the bill. TalkTalk stated that suspending access to the internet breached human rights. This view may be shared by many, as a survey carried out by the BBC found that 87% of internet users felt internet access should be the 'fundamental right of all people'.[61] Certainly, people require access to the internet for many aspects of their life for example shopping, online banking, education, work and even socialising. Furthermore, TalkTalk Director of Regulation, Andrew Heaney has acknowledged that file sharing is a problem but the answer is to educate people and create legal alternatives. Heaney has also argued that disconnected offenders will simply create other user names to hide their identity and continue downloading. TalkTalk has claimed that 80% of youngsters would continue to download regardless of the bill and that internet service providers are being forced to police this without any workable outcomes.[62]

- Cable company Virgin Media also criticized the Digital Economy Bill believing it to be heavy handed and likely to alienate customers. Virgin advocated the development of alternative services which people would choose instead of file sharing.[63]

The bill provoked protests in many forms. The Guardian reported that hundreds were expected to march outside the House of Commons on 24 March 2010.[64] Moreover, an estimated 12,000 people sent emails to their MPs, through the citizen advocacy organization 38 degrees. 38 degrees objected to the speed with which the bill was rushed through parliament, without proper debate, due to the imminent dissolution of parliament prior to a general election.[64] In October 2009 TalkTalk launched its Don't Disconnect Us campaign asking people to sign a petition against the proposal to cut off the internet connections of those accused of unauthorized file sharing.[65] By November 2009 the petition had almost 17,000 signatories[66] and by December had reached over 30,000.[67] The Pirate Party in the UK called for non-commercial file sharing to be legalized. Formed in 2009 and intending to enter candidates in the 2010 UK general election, the Pirate Party advocates reform to copyright and patent laws and a reduction in government surveillance.[68]

The Code which would implement these sections of the Act was never passed into law by Parliament, and no action was taken on it after around 2013.

Download Microsoft Visual Studio 2010 Full Version

- Digital Economy Act 2017

The Digital Economy Act 2017 updates the anti-infringement provisions of existing laws, creates or updates criminal copyright breach provisions, and provides for a wider range of sentencing for criminal infringement.

United States[edit]

In Sony Corp. v. Universal Studios, 464 U.S. 417 (1984), the Supreme Court found that Sony's new product, the Betamax (the first mass-market consumer videocassette recorder), did not subject Sony to secondary copyright liability because it was capable of substantial non-infringing uses. Decades later, this case became the jumping-off point for all peer-to-peer copyright infringement litigation.

The first peer-to-peer case was A&M Records v. Napster, 239 F.3d 1004 (9th Cir. 2001). Here, the 9th Circuit considered whether Napster was liable as a secondary infringer. First, the court considered whether Napster was contributorily liable for copyright infringement. To be found contributorily liable, Napster must have engaged in 'personal conduct that encourages or assists the infringement.'[69] The court found that Napster was contributorily liable for the copyright infringement of its end-users because it 'knowingly encourages and assists the infringement of plaintiffs' copyrights.'[70] The court analyzed whether Napster was vicariously liable for copyright infringement. The standard applied by the court was whether Napster 'has the right and ability to supervise the infringing activity and also has a direct financial interest in such activities.'[71] The court found that Napster did receive a financial benefit, and had the right and ability to supervise the activity, meaning that the plaintiffs demonstrated a likelihood of success on the merits of their claim of vicarious infringement.[72] The court denied all of Napster's defenses, including its claim of fair use.

The next major peer-to-peer case was MGM v. Grokster, 545 U.S. 913 (2005). In this case, the Supreme Court found that even if Grokster was capable of substantial non-infringing uses, which the Sony court found was enough to relieve one of secondary copyright liability, Grokster was still secondarily liable because it induced its users to infringe.[73][74]

It is important to note the concept of blame in cases such as these. In a pure P2P network there is no host, but in practice most P2P networks are hybrid. This has led groups such as the RIAA to file suit against individual users, rather than against companies. The reason that Napster was subject to violation of the law and ultimately lost in court was because Napster was not a pure P2P network but instead maintained a central server which maintained an index of the files currently available on the network.

Around the world in 2006, an estimated five billion songs, equating to approximately 38,000 years in music were swapped on peer-to-peer websites, while 509 million songs were purchased online. The same study which estimated these findings also found that artists that had an online presence ended up retaining more of the profits rather than the music companies.[75]

In November 2009, the U.S. House of Representatives introduced the Secure Federal File Sharing Act,[76] which would, if enacted, prohibit the use of peer-to-peer file-sharing software by U.S. government employees and contractors on computers used for federal government work.[77] The bill has died with the adjournment of 111th Congress.

Copyright law[edit]

A copyright in the United States consists of the exclusive rights enumerated under 17 USC 106.[78] When having to do with pictures, music, literature or video, these exclusive rights include:1. The right to reproduce or redistribute the picture, music, lyrics, text, video, or images of a video.2. The right to distribute the picture, music, lyrics, text, video, or images of a video.3. The right to produce derivative works of the copyrighted work.4. The right to perform the work publicly.5. The right to display the work publicly.6. The right to transmit the work through the use of radio or digital transition. In summary, these exclusive rights cover the reproduction, adaptation, publication, performance, and display of a copyrighted work (subject to limitations such as fair use).[79]

Anyone who violates the exclusive rights of copyright has committed copyright infringement, whether or not the work has been registered at the copyright office. If an infringement has occurred, the copyright owner has a legal right to sue the infringer for violating the terms of their copyright. The monetary value of the lawsuit can be whatever a jury decides is acceptable.

In the case of file sharing networks, companies claim that peer-to-peer file sharing enables the violation of their copyrights. File sharing allows any file to be reproduced and redistributed indefinitely. Therefore, the reasoning is that if a copyrighted work is on a file sharing network, whoever uploaded or downloaded the file is liable for violating the copyright because they are reproducing the work without the authorization of the copyright holder or the law.

Primary infringement liability[edit]

The fundamental question, 'what use can a P2P file-sharing network's customers make of the software and of copyrighted materials without violating copyright law', has no answer at this time, as there has been almost no dispositive decision-making on the subject.

This issue has received virtually no appellate attention, the sole exception being BMG Music v. Gonzalez,[80] a decision of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, which held that where a defendant has admitted downloading and copying song files from other users in the P2P network without permission of the copyright holders, she cannot claim that such copying is a 'fair use'. Since Gonzalez involves a defendant who had admitted to actual copying and downloading of songs from other unauthorized users, it is of limited applicability in contested cases, in that it relates solely to the reproduction right in 17 USC 106(1), and has no bearing on the 17 USC 106(3) distribution right.

A series of cases dealing with the RIAA's 'making available' theory has broad implications, not only for the subject of P2P file sharing but for the Internet at large. The first to receive a great deal of attention was Elektra v. Barker,[81] an RIAA case against Tenise Barker, a Bronx nursing student. Ms. Barker moved to dismiss the complaint, contending, among other things, that the RIAA's allegation of 'making available' did not state any known claim under the Copyright Act.[82][83] The RIAA countered with the argument that even without any copying, and without any other violation of the record companies' distribution rights, the mere act of 'making available' is a copyright infringement, even though the language does not appear in the Copyright Act, as a violation of the 'distribution' right described in 17 USC 106(3).[84] Thereafter, several amicus curiae were permitted to file briefs in the case, including the MPAA, which agreed[85] with the RIAA's argument, and the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), the U.S. Internet Industry Association (USIIA), and the Computer & Communications Industry Association (CCIA), which agreed with Ms. Barker.[86][87] The US Department of Justice submitted a brief refuting one of the arguments made by EFF,[88] but did not take any position on the RIAA's 'making available' argument, noting that it had never prosecuted anyone for 'making available'.[89] The Elektra v. Barker case was argued before Judge Kenneth M. Karas in Manhattan federal court on 26 January 2007,[90] and decided on 31 March 2008.[91]

The decision rejected the RIAA's 'making available' theory but sustained the legal sufficiency of the RIAA's pleading of actual distribution and actual downloading. Additionally, the Court suggested to the RIAA that it might want to amend its complaint to include a claim for 'offering to distribute for purposes of distribution', but gave no guidance on what type of evidence would be required for an 'offer'. The Court's suggestion that merely 'offering' to distribute could constitute a violation of the Act has come under attack from William Patry, the author of the treatise Patry on Copyright.[92]

Three other decisions, also rejecting the RIAA's 'making available' theory, came from more unexpected sources.

The Barker decision was perhaps rendered anticlimactic by the decision of Judge Janet Bond Arterton, from the District of Connecticut, handed down six weeks earlier, in Atlantic v. Brennan,[93] rejecting the RIAA's application for a default judgment. Brennan, like Barker, rejected the RIAA's 'making available' theory, but unlike Barker it found the RIAA's specificity on the other issues to be insufficient, and it rejected the conceptual underpinnings upon which Judge Karas based his 'offer to distribute' idea.

And Barker was perhaps overshadowed by the decision of Judge Gertner, rendered the same day as the Barker decision, in quashing a subpoena served on Boston University to learn the identity of BU students, in London-Sire v. Doe 1.[94] Here too the Court rejected the RIAA's 'making available' theory, but here too—like Atlantic but unlike Elektra – also rejected any possible underpinning for an 'offer to distribute' theory.

And then came the decision of the District Judge Neil V. Wake, in the District of Arizona, in Atlantic v. Howell.[95] This 17-page decision[96] – rendered in a case in which the defendant appeared pro se (i.e., without a lawyer) but eventually received the assistance of an amicus curiae brief and oral argument by the Electronic Frontier Foundation[97]—was devoted almost exclusively to the RIAA's 'making available' theory and to the 'offer to distribute' theory suggested by Judge Karas in Barker. Atlantic v. Howell strongly rejected both theories as being contrary to the plain wording of the Copyright Act. The Court held that 'Merely making a copy available does not constitute distribution....The statute provides copyright holders with the exclusive right to distribute 'copies' of their works to the public 'by sale or other transfer of ownership, or by rental, lease, or lending.' 17 U.S.C. ...106(3). Unless a copy of the work changes hands in one of the designated ways, a 'distribution' under ...106(3) has not taken place.' The Court also expressly rejected the 'offer to distribute' theory suggested in Barker, holding that 'An offer to distribute does not constitute distribution'.[98]

The next critical decision was that in Capitol v. Thomas, which had received a great deal of media attention because it was the RIAA's first case to go to trial, and probably additional attention due to its outsized initial jury verdict. The RIAA had prevailed upon the trial judge to give the jurors an instruction which adopted its 'making available' theory,[99] over the protestations of the defendant's lawyer. Operating under that instruction, the jury returned a $222,000 verdict over $23.76 worth of song files.[100] Almost a year after the jury returned that verdict, however, District Judge Michael J. Davis set the verdict aside, and ordered a new trial, on the ground that his instruction to the jurors—that they did not need to find that any files were actually distributed in order to find a violation of plaintiffs' distribution right—was a 'manifest error of law'.[101] The Judge's 44-page decision agreed with Howell and London-Sire and rejected so much of Barker as intimated the existence of a viable 'offer to distribute' theory.

There may be indications that the RIAA has been jettisoning its 'making available' theory. In a San Diego, California, case, Interscope v. Rodriguez, where the Judge dismissed the RIAA's complaint as 'conclusory', 'boilerplate', 'speculation', the RIAA filed an amended complaint which contained no reference at all to 'making available'.[102] In subsequent cases, the RIAA's complaint abandoned altogether the 'making available' theory, following the model of the Interscope v. Rodriguez amended complaint.

In its place, it is apparently adopting the 'offer to distribute' theory suggested by Judge Karas. In the amended complaint the RIAA filed in Barker, it deleted the 'making available' argument—as required by the judge—but added an 'offer to distribute' claim, as the judge had suggested.[103] It remains to be seen if it will follow that pattern in other cases.

Secondary infringement liability[edit]

Secondary liability, the possible liability of a defendant who is not a copyright infringer but who may have encouraged or induced copyright infringement by another, has been discussed generally by the United States Supreme Court in MGM v. Grokster,[74] which held in essence that secondary liability could only be found where there has been affirmative encouragement or inducing behavior. On remand, the lower court found Streamcast, the maker of Morpheus software, to be liable for its customers' copyright infringements, based upon the specific facts of that case.[104]

Under US law 'the Betamax decision' (Sony Corp. of America v. Universal City Studios, Inc.), holds that copying 'technologies' are not inherently illegal, if substantial non-infringing use can be made of them. Although this decision predated the widespread use of the Internet, in MGM v. Grokster, the U.S. Supreme Court acknowledged the applicability of the Betamax case to peer-to-peer file sharing, and held that the networks could not be liable for merely providing the technology, absent proof that they had engaged in 'inducement.'

In 2006 the RIAA initiated its first major post-Grokster, secondary liability case, against LimeWire in Arista Records LLC v. Lime Group LLC, where the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York held that LimeWire induced copyright infringement and granted a permanent injunction against LimeWire.

Electronic Frontier Foundation[edit]

The Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) seeks to protect and expand digital rights through litigation, political lobbying, and public awareness campaigns. The EFF has vocally opposed the RIAA in its pursuit of lawsuits against users of file sharing applications and supported defendants in these cases. The foundation promotes the legalization of peer-to-peer sharing of copyrighted materials and alternative methods to provide compensation to copyright holders.[105]

In September 2008 the organization marked the 5th 'anniversary' of the RIAA's litigation campaign by publishing a highly critical, detailed report, entitled 'RIAA v. The People: Five Years Later',[106] concluding that the campaign was a failure.

Reported suspension of RIAA litigation campaign[edit]

Several months later, it was reported that the RIAA was suspending its litigation campaign,[107] followed by a report that it had fired the investigative firm SafeNet (formerly MediaSentry) operating on its behalf.[108] Some of the details of the reports, including claims that the RIAA had actually stopped commencing new lawsuits months earlier, and that its reason for doing so was that it had entered into tentative agreements with Internet service providers to police their customers, proved to be either inaccurate or impossible to verify[109] and RIAA's claim not to have filed new cases 'for months' was false.[110]

Effects[edit]

A study ordered by the European Union found that illegal downloading may lead to an increase in overall video game sales because newer games charge for extra features or levels. The paper concluded that piracy had a negative financial impact on movies, music, and literature. The study relied on self-reported data about game purchases and use of illegal download sites. Pains were taken to remove effects of false and misremembered responses.[111][112][113]

Notable cases[edit]

- EU

- Atari Europe S.A.S.U. v. Rapidshare AG (Germany)

- OiNK's Pink Palace (England)

- USA

- The AACS encryption key controversy of 2007

- Flava Works Inc. v. Gunter - appeal case which analyzed contributory infringement in the context of linking to infringing material and social bookmarking.

- Sony Corp. v. Universal City Studios (The Betamax decision)

- Sweden

- Singapore

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^'RIAA joins congressional caucus in unveiling first-ever list of notorious illegal sites'. RIAA. 19 May 2010. Archived from the original on 23 April 2011. Retrieved 16 January 2011.

- ^Roettgers, Janko (3 May 2010). 'RapidShare Wins in Court'. Gigaom.com. Archived from the original on 26 February 2011. Retrieved 16 January 2011. - cite from ruling: 'Es ist davon auszugehen, dass die weit überwiegende Zahl von Nutzern die Speicherdienste zu legalen Zwecken einsetzen und die Zahl der missbräuchlichen Nutzer in der absoluten Minderheit ist.' (It is to be expected that the vast majority of users use the storage services for lawful purposes and the number of abusive users are in the absolute minority.)

- ^From the Atari v. RapidShare ruling: 'entspricht einem Generalverdacht gegen Sharehoster-Dienste und ihre Nutzer, der so nicht zu rechtfertigen ist' (corresponds to a general suspicion against shared hosting services and their users, which is not to justify such)

- ^Legal case: OLG Dusseldorf, Judgement of 22 March 2010, Az I-20 U 166/09 dated 22 March 2010.

- ^Department of Justice indictment, on Wall Street Journal's websiteArchived 15 July 2012 at Archive.today - see sections 7 - 14.

- ^Moya, Jared (4 January 2008). 'China to Require Video File-Sharing sites to get permits?'. Zeropaid. Archived from the original on 5 October 2010. Retrieved 26 May 2010.

- ^'China Shuts Down File-Sharing Site'. Canadian Broadcasting Company. 9 September 2009. Archived from the original on 4 October 2010. Retrieved 26 May 2010.

- ^Moya, Jared (8 December 2009). 'China Shutters BitTorrent Sites Over Porn, Copyrighted Material'. Zeropaid. Archived from the original on 11 February 2010. Retrieved 26 May 2010.

- ^'Good news everyone: after 5 years, we now know that what we do every day is legal…No, seriously'. Copyright for Creativity: A Declaration for Europe. Archived from the original on 20 December 2014. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- ^'CJEU Judgment: No Copyright Infringement in Mere Web Viewing'. www.scl.org. SCL - The IT Law Community (UK). Archived from the original on 20 December 2014. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- ^Meyer, David. 'You can't break copyright by looking at something online, Europe's top court rules'. Gigaom. Archived from the original on 27 October 2014. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- ^'Case C‑360/13'. Court of Justice of the European Union. Court of Justice of the European Union. Archived from the original on 20 December 2014. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- ^Smith, Chris. 'Pirating copyrighted content is legal in Europe, if done correctly'. www.bgr.com. Boy Genius Report. Archived from the original on 19 December 2014. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- ^European MPs votes on new telecoms law, 24 November 2009

- ^Herseth Kaldestad, Oyvind (9 September 2008). 'Norwegian Consumer Council calls for Internet complaint board'. Forbrukerradet. Archived from the original on 27 October 2008.

- ^ abcdKlosek, Jacqueline (9 October 2008). 'United States: Combating Piracy And protecting privacy: A European Perspective'. Mondaq. Archived from the original on 14 October 2008.

- ^Herseth Kaldestad, Oyvind (28 February 2008). 'ISP liability: Norwegian Consumer Council warns consumers not to sign letter of guilt'. Forbrukerradet. Archived from the original on 26 October 2008.

- ^'Government presents controversial file sharing bill'. Archived from the original on 1 March 2009. Retrieved 31 January 2009.

- ^France Approves Wide Crackdown on Net Piracy. Pfanner, Eric (2009). https://www.nytimes.com/2009/10/23/technology/23net.html?_r=2/Archived 8 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^Siraj Datoo (9 July 2013). 'France drops controversial 'Hadopi law' after spending millions'. The Guardian. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 26 December 2013.

- ^'Inside Ireland'. 28 March 2012. Archived from the original on 28 March 2012.

- ^Shirley Gene Field (2010). 'Internet Piracy in Japan: Lessig’s Modalities of Constraint and Japanese File Sharing'.Archived 7 April 2014 at the Wayback MachineUniversity of Texas Masters Thesis.

- ^ ab'Japan introduces piracy penalties for illegal downloads'.Archived 19 April 2014 at the Wayback MachineBBC.

- ^George Ou (16 March 2008). 'Japan's ISPs agree to ban P2P pirates'.Archived 7 April 2014 at the Wayback MachineZDNet, .

- ^'No more free downloads as MCMC blocks 10 file sharing sites'. The Star (Malaysia). 11 June 2011. Archived from the original on 20 April 2013. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- ^'In Mexico, music piracy rising with broadband'. MSNBC. 7 July 2006. Archived from the original on 12 November 2017. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- ^International Intellectual Property Alliance (18 February 2010). '2010 special 301 report on copyright protection and enforcement'(PDF). MEXICO. Mexico: 66. Retrieved 27 May 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^interactive, 4net. 'top free hosting'. brightcobracenter.com. Archived from the original on 25 October 2012.

- ^ abJeremy Hsu (22 May 2012). 'Illegal File-Sharing Opens North Korea to World'.Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback MachineYahoo! News.

- ^ abIan Steadman (6/08/2012). 'Report finds rampant filesharing in North Korea, despite the risks'.Archived 7 April 2014 at the Wayback MachineWired.

- ^Moya, Jared (23 July 2009). 'South Korea's 'Three-Strikes' Law Takes Effect'. Zero Paid. Archived from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 23 September 2013.

- ^Barry, Sookman; Dan Glover (20 January 2010). 'Graduated response and copyright: an idea that is right for the times'. Archived from the original on 12 June 2010. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^Tong-hyung, Kim (23 July 2009). 'Upload a Song, Lose your Internet Connection'. Korea Times. Archived from the original on 27 May 2010. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^'Spanish judge says downloading is legal'. Archived from the original on 15 September 2008. Retrieved 27 August 2008.

- ^'Spanish court decides linking to P2P downloads is legal'. Archived from the original on 27 September 2008. Retrieved 27 August 2008.

- ^'Del '¿Por qué no te callas?' al 'No pasa nada, podéis bajar lo que queráis del eMule''. Archived from the original on 22 June 2008. Retrieved 27 August 2008.

- ^'Manifestación a favor del intercambio de archivos frente a la sede del PSOE'. Archived from the original on 23 February 2009. Retrieved 12 March 2009.

- ^'Operation Teddy: P2P sharing is not illegal'. Retrieved 27 August 2008.

- ^'Compartir Es Bueno! Lo hemos hecho! Y nadie nos ha detenido'. Archived from the original on 14 September 2008. Retrieved 27 August 2008.

- ^'Spanish copyright society hounds Uni teacher out of job'. Archived from the original on 2 June 2008. Retrieved 27 August 2008.

- ^'Jorge Cortell – Descargar y copiar música es legal y bueno'. Archived from the original on 10 February 2009. Retrieved 27 August 2008.

- ^'Downloading files from p2p networks is legal in Spain'. Archived from the original on 1 February 2009. Retrieved 17 February 2009.

- ^Downloading 3322 Copyrighted Movies is Okay in SpainArchived 31 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine, at TorrentFreak

- ^ abSpain finds that film piracy is a hard habit to break. Tremlett, Giles (2010). 'Spain finds that film piracy is a hard habit to break'. Archived from the original on 4 February 2011. Retrieved 16 January 2011..

- ^Allen, Katie. Piracy continues to cripple music industry as sales fall 10%Archived 7 April 2017 at the Wayback MachineThe Guardian. 21 January 2010.

- ^El número de conciertos en España y la recaudación por venta de entradas se multiplicaron por dos en la última década. 'Últimas noticias'. Archived from the original on 30 December 2010. Retrieved 16 January 2011.

- ^File Sharing and Torrent Websites Now Legal in Spain. Wilhelm, Alex. (2010). 'File Sharing And Torrent Websites Now Legal In Spain'. Archived from the original on 22 July 2010. Retrieved 16 January 2011.

- ^Mike Butcher (21 September 2013). 'Spanish Pirate Site Owners To Get 6 Years Of Jail Time, But Users Off The Hook'. TechCrunch. AOL Inc. Archived from the original on 25 September 2013. Retrieved 23 September 2013.

- ^'Progress of the Digital Economy Bill'. Interactive.bis.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 27 May 2010. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- ^'International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IPFI) Digital Music Report 2009'. Ifpi.org. 16 January 2009. Archived from the original on 7 December 2011. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- ^Rory Cellan-Jones (27 November 2009). 'Cellan-Jones, Rory (2009) 'Facts about file-sharing' BBC NEWS 27th November 2009'. BBC. Archived from the original on 23 August 2011. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- ^Emma Barnett (9 April 2010). 'Digital Economy Act: what happens next?'. The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 3 June 2010.

- ^'Mother to settle web music charge BBC News 20th August 2005'. BBC News. 20 August 2005. Archived from the original on 13 December 2006. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- ^Digital Economy BillArchived 30 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^'Digital Economy Bill Copyright Factsheet November 2009'. Interactive.bis.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 2 April 2010. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- ^ abJohnson, Bobbie (16 March 2010). 'Concern as Lords Pass Digital Economy Bill to Lords'. The Guardian. UK. Archived from the original on 8 December 2013. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- ^Charles Arthur (8 April 2010). 'Arthur, Charles (2010) 'Digital Economy Bill rushed through Wash-Up in late night session' The Guardian'. The Guardian. UK. Archived from the original on 10 September 2013. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- ^Phillips, Tom (8 April 2010). 'Phillips, Tom (2010) Digital Economy Bill passes as critics warn of 'catastrophic disaster' Metro'. Metro.co.uk. Archived from the original on 7 September 2011. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- ^Britz, J. J. (2002). Information Ethics: its Demarcation and Application. In: Lipinski, T. A. (eds.) Libraries, Museums, and Archives: Legal and Ethical Challenges in the New Era of Information. Maryland: The Scarecrow Press. pp. 194–219.

- ^Arthur, C. (2010). Opposition to the Digital Economy Bill. The Guardian. Availability: 'Archived copy'. Archived from the original on 20 July 2012. Retrieved 4 October 2016.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link). Last accessed 30 March 2010.

- ^'Internet access is a fundamental right BBC News'. BBC News. 8 March 2010. Archived from the original on 20 October 2011. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- ^'Music fans will sidestep filesharing clampdown says TalkTalk' TalkTalk Press Centre 15 March 2010Archived 25 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^Technology (25 August 2009). 'Andrews, Amanda (2009) 'BT and Virgin Media attack Government plans to curb illegal downloading' Telegraph 25th August 2009'. The Daily Telegraph. UK. Archived from the original on 25 December 2013. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- ^ abArthur, Charles (24 March 2010). 'Hundreds expected outside parliament to protest at digital economy bill'. The Guardian. UK. Archived from the original on 21 January 2016. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- ^'Don't Disconnect Us campaign group website'. Dontdisconnect.us. Archived from the original on 27 December 2011. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- ^'Beaumont, Claudine (2009) 'Stephen Fry backs Digital Economy Bill protests' Telegraphy 14th November 2009'. The Daily Telegraph. UK. 24 November 2009. Archived from the original on 24 February 2011. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- ^'Heaney, Andrew (2009) 'Our Don't Disconnect Us petition passes 30,000 signatories' TalkTalk Blog'. Talktalkblog.co.uk. 14 December 2009. Archived from the original on 24 January 2012. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- ^Pirate Party Official website, 'Archived copy'. Archived from the original on 5 January 2011. Retrieved 16 January 2011.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

- ^A&M Records v. Napster, Inc., 239 F.3d 1004, 1019 (9th Cir. 2001) citing Matthew Bender & Co. v. West Publ'g Co., 158 F.3d 693, 706 (2d Cir. 1998)

- ^Napster, at 1020.

- ^Napster, at 1022, citingGershwin Publ'g Corp. v. Columbia Artists Mgmt., Inc, 443 F.2d 1159, 1162 (2d Cir. 1971.

- ^Napster, at 1024.

- ^MGM v. Grokster, 514 U.S. 913, 940 (2005).

- ^ ab'MGM v. Grokster'. Recordingindustryvspeople.blogspot.com. 30 June 2010. Archived from the original on 24 January 2012. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- ^June 2008, The Tables Have Turned: Rock Stars – Not Record Labels – Cashing In On Digital Revolution[permanent dead link], IBISWorld

- ^H.R. 4098, The Secure Federal File Sharing Act, introduced 17 November 2009

- ^Richard Lardner (18 November 2009). 'House Pushes Ban On Peer-To-Peer Software For Federal Employees'. Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 20 November 2009. Retrieved 18 November 2009.

- ^'17 USC 106'. Caselaw.lp.findlaw.com. Archived from the original on 28 August 2009. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- ^'17 USC 106 notes'. Codes.lp.findlaw.com. Archived from the original on 9 March 2012. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- ^'BMG v. Gonzalez'. Recordingindustryvspeople.blogspot.com. 30 June 2010. Archived from the original on 24 January 2012. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- ^'Elektra v. Barker'. Recordingindustryvspeople.blogspot.com. 30 June 2010. Archived from the original on 24 January 2012. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- ^'Elektra v. Barker, Memorandum of Law in Support of Motion to Dismiss Complaint'. Ilrweb.com. Archived from the original on 5 January 2009. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- ^'Reply Memorandum of Law in Support of Motion to Dismiss Complaint'. Ilrweb.com. Archived from the original on 5 January 2009. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- ^'Elektra v. Barker, Plaintiffs' Memorandum of Law in Opposition to Dismissal Motion'. Ilrweb.com. Archived from the original on 5 January 2009. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- ^'Amicus Curiae brief of MPAA'. Ilrweb.com. Archived from the original on 5 January 2009. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- ^'Amicus Curiae brief of EFF'. Ilrweb.com. Archived from the original on 5 January 2009. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- ^'Amicus Curiae brief of USIIA and CCIA'. Ilrweb.com. Archived from the original on 5 January 2009. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- ^'Statement of Interest of U.S. Department of Justice'. Ilrweb.com. Archived from the original on 18 January 2010. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- ^'Statement of Interest, page 5, footnote 3'. Ilrweb.com. Archived from the original on 18 January 2010. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- ^'Elektra v. Barker 'Making Available' Oral Argument Now Available Online'Archived 18 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Recording Industry vs. The People, 27 February 2007

- ^'Judge rejects RIAA 'making available' theory but sustains complaint, and gives RIAA chance to replead defective theory in Elektra v. Barker'Archived 5 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Recording Industry vs. The People, 31 March 2008.

- ^'The recent making available cases'Archived 26 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine, The Patry Copyright Blog, 3 April 2008.

- ^'Default judgment denied in Atlantic v. Brennan, RIAA complaint insufficient, possible defenses of copyright misuse, excessive damages'Archived 28 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Recording Industry vs. The People, 25 February 2008.

- ^'RIAA's Boston University Subpoena Quashed in Arista v. Does 1–21'Archived 10 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Recording Industry vs. The People, 3 April 2008.

- ^'Atlantic v. Howell'. Recordingindustryvspeople.blogspot.com. 30 June 2010. Archived from the original on 24 January 2012. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- ^'RIAA summary judgment motion denied in Atlantic v. Howell; RIAA 'making available' theory & Judge Karas 'offer to distribute' theory rejected'Archived 2 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Recording Industry vs. The People, 29 April 2008

- ^'Jeffrey Howell is not alone; Electronic Frontier Foundation files amicus curiae brief refuting RIAA arguments in Atlantic v. Howell'Archived 16 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Recording Industry vs. The People, 12 January 2008

- ^For commentary on Atlantic v. Howell see 'Atlantic Recording Corp. v. Howell'Archived 6 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine, The Patry Copyright Blog, 30 April 2008. For the amicus curiae brief submitted by the Electronic Frontier Foundation in support of Mr. Howell, see 'Jeffrey Howell is not alone; Electronic Frontier Foundation files amicus curiae brief refuting RIAA arguments in Atlantic v. Howell'Archived 16 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Recording Industry vs. The People, 12 January 2008

- ^'Jury Instructions in Virgin v. Thomas Available Online'Archived 16 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine Recording Industry vs. The People, 5 October 2007 (See instruction number 15)

- ^'RIAA Wins in First-Ever Jury Trial; Verdict of $222,000 for 24 Song Files Worth $23.76'Archived 20 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Recording Industry vs. The People, 4 October 2007.

- ^'RIAA's $222,000 verdict in Capitol v. Thomas set aside. Judge rejects 'making available'; attacks excessive damages.'Archived 28 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Recording Industry vs. The People, 24 September 2008.

- ^'RIAA Abandons 'Making Available' in Amended Complaint in Rodriguez caseArchived 21 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine', Recording Industry vs. The People, 10 September 2007.

- ^'Amended complaint filed in Elektra v. Barker'Archived 16 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Recording Industry vs. The People, 2 May 2008.

- ^'Streamcast Held Liable for Copyright Infringement in MGM v. Grokster, Round 2Archived 25 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine', Recording Industry vs. The People, 30 September 2006.

- ^Electronic Frontier Foundation. 'Making P2P Pay Artists'. Archived from the original on 25 April 2006. Retrieved 25 April 2006.

- ^'RIAA v. The People: Five Years Later'. Eff.org. Archived from the original on 7 October 2011. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- ^'p2pnet reports that RIAA dropping 'mass lawsuits' to look for 'more effective ways' to combat copyright infringement'Archived 7 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Recording Industry vs. The People, 19 December 2008.

- ^'Wall Street Journal confirms that RIAA dumped MediaSentry'Archived 8 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Recording Industry vs. The People, 4 January 2009

- ^'Recording Industry vs. The People'. Recordingindustryvspeople.blogspot.com. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- ^'Recording Industry vs. The People'. Recordingindustryvspeople.blogspot.com. Archived from the original on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- ^'Illegal downloads may not actually harm sales, but the European Union doesn't want you to know that'. 22 September 2017. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017.

- ^Polgar, David Ryan. 'Does Video Game Piracy Actually Result in More Sales?'. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017.

- ^'EU study finds piracy doesn't hurt game sales, may actually help'. Archived from the original on 1 October 2017.

Top 4 Download periodically updates software information of visual basic 2010 full versions from the publishers, but some information may be slightly out-of-date.

Using warez version, crack, warez passwords, patches, serial numbers, registration codes, key generator, pirate key, keymaker or keygen for visual basic 2010 license key is illegal. Download links are directly from our mirrors or publisher's website, visual basic 2010 torrent files or shared files from free file sharing and free upload services, including Rapidshare, MegaUpload, YouSendIt, Letitbit, DropSend, MediaMax, HellShare, HotFile, FileServe, LeapFile, MyOtherDrive or MediaFire, are not allowed!

Your computer will be at risk getting infected with spyware, adware, viruses, worms, trojan horses, dialers, etc while you are searching and browsing these illegal sites which distribute a so called keygen, key generator, pirate key, serial number, warez full version or crack for visual basic 2010. These infections might corrupt your computer installation or breach your privacy. visual basic 2010 keygen or key generator might contain a trojan horse opening a backdoor on your computer.

Jump to navigationJump to search| Part of a series on |

| File sharing |

|---|

| Technologies |

| Video sharing sites |

| BitTorrent sites |

| Academic/scholarly |

| File sharing networks |

| P2P clients |

| Streaming programs |

| Anonymous file sharing |

| Development and societal aspects |

| By country or region |

| Comparisons |

BitTorrent (abbreviated to BT) is a communication protocol for peer-to-peer file sharing (P2P) which is used to distribute data and electronic files over the Internet.

BitTorrent is one of the most common protocols for transferring large files, such as digital video files containing TV shows or video clips or digital audio files containing songs. Peer-to-peer networks have been estimated to collectively account for approximately 43% to 70% of all Internet traffic (depending on location) as of February 2009.[1] In February 2013, BitTorrent was responsible for 3.35% of all worldwide bandwidth, more than half of the 6% of total bandwidth dedicated to file sharing.[2]

To send or receive files, a person uses a BitTorrent client on their Internet-connected computer. A BitTorrent client is a computer program that implements the BitTorrent protocol. Popular clients include μTorrent, Xunlei,[3]Transmission, qBittorrent, Vuze, Deluge, BitComet and Tixati. BitTorrent trackers provide a list of files available for transfer, and allow the client to find peer users known as seeds who may transfer the files.

Programmer Bram Cohen, a former University at Buffalo student,[4] designed the protocol in April 2001 and released the first available version on 2 July 2001,[5] and the most recent version in 2013.[6]BitTorrent clients are available for a variety of computing platforms and operating systems including an official client released by BitTorrent, Inc.

As of 2013, BitTorrent has 15–27 million concurrent users at any time.[7]As of January 2012, BitTorrent is utilized by 150 million active users. Based on this figure, the total number of monthly BitTorrent users may be estimated to more than a quarter of a billion.[8]

- 2Operation

- 3Adoption

- 5Technologies built on BitTorrent

- 5.2Web seeding

- 11Malware

- 11.1BitErrant attack

Description[edit]

The BitTorrent protocol can be used to reduce the server and network impact of distributing large files. Rather than downloading a file from a single source server, the BitTorrent protocol allows users to join a 'swarm' of hosts to upload to/download from each other simultaneously. The protocol is an alternative to the older single source, multiple mirror sources technique for distributing data, and can work effectively over networks with lower bandwidth. Using the BitTorrent protocol, several basic computers, such as home computers, can replace large servers while efficiently distributing files to many recipients. This lower bandwidth usage also helps prevent large spikes in internet traffic in a given area, keeping internet speeds higher for all users in general, regardless of whether or not they use the BitTorrent protocol. A user who wants to upload a file first creates a small torrent descriptor file that they distribute by conventional means (web, email, etc.). They then make the file itself available through a BitTorrent node acting as a seed. Those with the torrent descriptor file can give it to their own BitTorrent nodes, which—acting as peers or leechers—download it by connecting to the seed and/or other peers (see diagram on the right).

The file being distributed is divided into segments called pieces. As each peer receives a new piece of the file, it becomes a source (of that piece) for other peers, relieving the original seed from having to send that piece to every computer or user wishing a copy. With BitTorrent, the task of distributing the file is shared by those who want it; it is entirely possible for the seed to send only a single copy of the file itself and eventually distribute to an unlimited number of peers. Each piece is protected by a cryptographic hash contained in the torrent descriptor.[6] This ensures that any modification of the piece can be reliably detected, and thus prevents both accidental and malicious modifications of any of the pieces received at other nodes. If a node starts with an authentic copy of the torrent descriptor, it can verify the authenticity of the entire file it receives.

Microsoft Visual Studio 2010 Iso

Pieces are typically downloaded non-sequentially and are rearranged into the correct order by the BitTorrent client, which monitors which pieces it needs, and which pieces it has and can upload to other peers. Pieces are of the same size throughout a single download (for example a 10 MB file may be transmitted as ten 1 MB pieces or as forty 256 KB pieces).Due to the nature of this approach, the download of any file can be halted at any time and be resumed at a later date, without the loss of previously downloaded information, which in turn makes BitTorrent particularly useful in the transfer of larger files. This also enables the client to seek out readily available pieces and download them immediately, rather than halting the download and waiting for the next (and possibly unavailable) piece in line, which typically reduces the overall time of the download. Once a peer has downloaded a file completely, it becomes an additional seed. This eventual transition from peers to seeders determines the overall 'health' of the file (as determined by the number of times a file is available in its complete form).

The distributed nature of BitTorrent can lead to a flood-like spreading of a file throughout many peer computer nodes. As more peers join the swarm, the likelihood of a completely successful download by any particular node increases. Relative to traditional Internet distribution schemes, this permits a significant reduction in the original distributor's hardware and bandwidth resource costs. Distributed downloading protocols in general provide redundancy against system problems, reduce dependence on the original distributor[9] and provide sources for the file which are generally transient and therefore harder to trace by those who would block distribution compared to the situation provided by limiting availability of the file to a fixed host machine (or even several).

One such example of BitTorrent being used to reduce the distribution cost of file transmission is in the BOINC client-server system. If a BOINC distributed computing application needs to be updated (or merely sent to a user), it can do so with little impact on the BOINC server.[10]

Operation[edit]

A BitTorrent client is any program that implements the BitTorrent protocol. Each client is capable of preparing, requesting, and transmitting any type of computer file over a network, using the protocol. A peer is any computer running an instance of a client. To share a file or group of files, a peer first creates a small file called a 'torrent' (e.g. MyFile.torrent). This file contains metadata about the files to be shared and about the tracker, the computer that coordinates the file distribution. Peers that want to download the file must first obtain a torrent file for it and connect to the specified tracker, which tells them from which other peers to download the pieces of the file.

Though both ultimately transfer files over a network, a BitTorrent download differs from a classic download (as is typical with an HTTP or FTP request, for example) in several fundamental ways:

- BitTorrent makes many small data requests over different IP connections to different machines, while classic downloading is typically made via a single TCP connection to a single machine.

- BitTorrent downloads in a random or in a 'rarest-first'[11] approach that ensures high availability, while classic downloads are sequential.

Taken together, these differences allow BitTorrent to achieve much lower cost to the content provider, much higher redundancy, and much greater resistance to abuse or to 'flash crowds' than regular server software. However, this protection, theoretically, comes at a cost: downloads can take time to rise to full speed because it may take time for enough peer connections to be established, and it may take time for a node to receive sufficient data to become an effective uploader. This contrasts with regular downloads (such as from an HTTP server, for example) that, while more vulnerable to overload and abuse, rise to full speed very quickly and maintain this speed throughout. In general, BitTorrent's non-contiguous download methods have prevented it from supporting progressive download or 'streaming playback'. However, comments made by Bram Cohen in January 2007[12] suggest that streaming torrent downloads will soon be commonplace and ad supported streaming[13] appears to be the result of those comments. In January 2011 Cohen demonstrated an early version of BitTorrent streaming, saying the feature was projected to be available by summer 2011.[14]As of 2013, this new BitTorrent streaming protocol is available for beta testing.[15]

Creating and publishing torrents[edit]

The peer distributing a data file treats the file as a number of identically sized pieces, usually with byte sizes of a power of 2, and typically between 32 kB and 16 MB each. The peer creates a hash for each piece, using the SHA-1 hash function, and records it in the torrent file. Pieces with sizes greater than 512 kB will reduce the size of a torrent file for a very large payload, but is claimed to reduce the efficiency of the protocol.[16] When another peer later receives a particular piece, the hash of the piece is compared to the recorded hash to test that the piece is error-free.[6] Peers that provide a complete file are called seeders, and the peer providing the initial copy is called the initial seeder. The exact information contained in the torrent file depends on the version of the BitTorrent protocol. By convention, the name of a torrent file has the suffix .torrent. Torrent files have an 'announce' section, which specifies the URL of the tracker, and an 'info' section, containing (suggested) names for the files, their lengths, the piece length used, and a SHA-1hash code for each piece, all of which are used by clients to verify the integrity of the data they receive. Though SHA-1 has shown signs of cryptographic weakness, Bram Cohen did not initially consider the risk big enough for a backward incompatible change to, for example, SHA-3. BitTorrent is now preparing to move to SHA-256.

Torrent files are typically published on websites or elsewhere, and registered with at least one tracker. The tracker maintains lists of the clients currently participating in the torrent.[6] Alternatively, in a trackerless system (decentralized tracking) every peer acts as a tracker. Azureus was the first[17] BitTorrent client to implement such a system through the distributed hash table (DHT) method. An alternative and incompatible DHT system, known as Mainline DHT, was released in the Mainline BitTorrent client three weeks later (though it had been in development since 2002)[17] and subsequently adopted by the µTorrent, Transmission, rTorrent, KTorrent, BitComet, and Deluge clients.

After the DHT was adopted, a 'private' flag – analogous to the broadcast flag – was unofficially introduced, telling clients to restrict the use of decentralized tracking regardless of the user's desires.[18] The flag is intentionally placed in the info section of the torrent so that it cannot be disabled or removed without changing the identity of the torrent. The purpose of the flag is to prevent torrents from being shared with clients that do not have access to the tracker. The flag was requested for inclusion in the official specification in August 2008, but has not been accepted yet.[19] Clients that have ignored the private flag were banned by many trackers, discouraging the practice.[20]

Downloading torrents and sharing files[edit]

Users find a torrent of interest, by browsing the web or by other means, download it, and open it with a BitTorrent client. The client connects to the tracker(s) specified in the torrent file, from which it receives a list of peers currently transferring pieces of the file(s) specified in the torrent. The client connects to those peers to obtain the various pieces. If the swarm contains only the initial seeder, the client connects directly to it and begins to request pieces. Clients incorporate mechanisms to optimize their download and upload rates; for example they download pieces in a random order to increase the opportunity to exchange data, which is only possible if two peers have different pieces of the file.

The effectiveness of this data exchange depends largely on the policies that clients use to determine to whom to send data. Clients may prefer to send data to peers that send data back to them (a 'tit for tat' exchange scheme), which encourages fair trading. But strict policies often result in suboptimal situations, such as when newly joined peers are unable to receive any data because they don't have any pieces yet to trade themselves or when two peers with a good connection between them do not exchange data simply because neither of them takes the initiative. To counter these effects, the official BitTorrent client program uses a mechanism called 'optimistic unchoking', whereby the client reserves a portion of its available bandwidth for sending pieces to random peers (not necessarily known good partners, so called preferred peers) in hopes of discovering even better partners and to ensure that newcomers get a chance to join the swarm.[21]